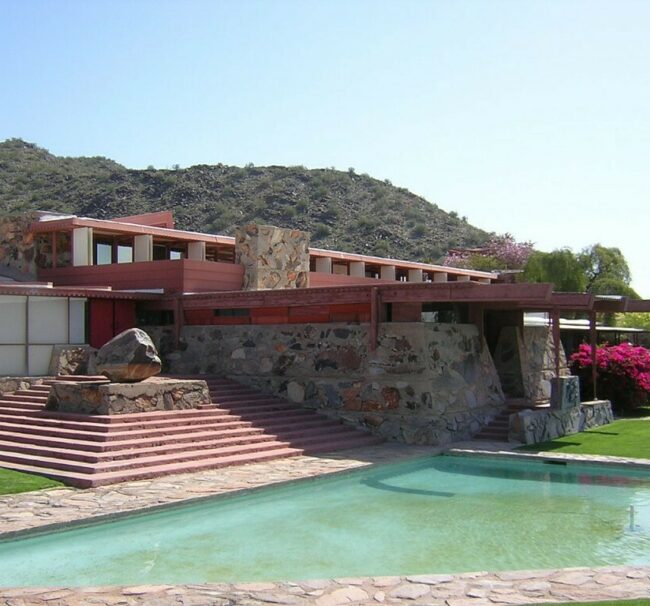

Taliesin West

According to Evelyn Lee on Inhabitat, the 600-square-foot, one-bedroom prefab prototype was built entirely by students, with guidance and input from faculty members. Says Lee, “The goal of the collaboration was to build a prototype prefab conducive to elegant and sustainable living within the heart of the desert landscape.” The structure makes use of lightweight panelized construction, rainwater collection and greywater reuse, solar panels, low-consumption fixtures and natural ventilation.

Mod.Fab has won several awards, includingTime’s Green Design 100 and Sunset magazine’s 2010 Best Green Home award. It’s a true organic oasis in the desert — one of many simple, efficient, natural homes popping up throughout the American West.

Another such home is a little (very little) structure that designer Dave Frazee calls “Miner’s Shelter.” This micro-home was built atop an authentic abandoned miner’s shelter. “Frazee constructed the home using concrete, steel, and locally sourced wood to reflect the desert environment,” writes Ashley Collman on the UK’s Daily Mail website. “The original miner’s shelter had a concrete chimney ready-built, so Frazee used it as a basis to keep the hut warm on cold nights by putting the door right next to the heat source. [He] designed the home with the desert climate in mind. Pop-out windows allow a breeze to come in and chill the room down on hot days. Inside the home, there’s just enough room for a bed.”

Frazee, now a member of the Broken Arrow Workshop (made up of Frank Lloyd Wright grads), built the structure as a temporary project while he was a student at Taliesin West. The home has since been approved to remain as a permanent structure.

On the other side of the country, near Pittsburgh, lies what many consider to be Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece: Fallingwater. Built in 1935 for wealthy business owner and philanthropist Edgar Kaufmann, Fallingwater is a brilliant marriage of nature and design.

Britton Marketing & Design Group president Jeff Britton recalls his impressions of this legendary architectural creation: “When I was at Fallingwater, I learned that the color of the house was the same shade as the undersides of the leaves that surround the home. It is a unique shade of yellow-mauve melon. When we were designing our own home, we didn’t want to repaint it, so we matched the color of lichen bark and the yellowish tips of new leaves in the spring with the wallpaper and some of the furnishings.”

And the Brittons’ home, nestled in a beautiful setting that borders a nature preserve in northeast Indiana, can certainly be considered organic in its design. With custom architecture that makes use of large, sunlight-friendly windows, as well as recently added geothermal power, the home peacefully coexists with its surroundings.

Reflecting on the natural aspects of his home, Britton says, “In the summer, there is so much green coming in the windows that if you turn around and look at the white wall, you get flashes of red — the complementary color of green, of course. Red is the opposite of the greenness of the forest. It is why Wright liked that Cherokee red and why the Japanese choose this color for ironwork in their gardens — yin yang.”